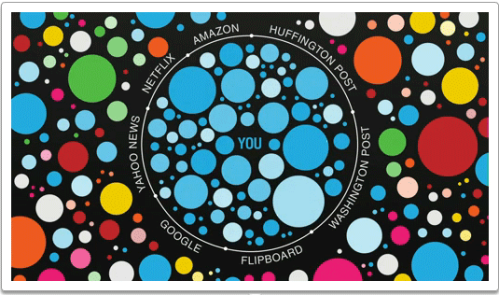

Pokemon Go has taken the planet by storm. In its firstweek it surpassed Twitter for daily active users, it became the top grossing US iPhone app in just 13 hours (despite being a free to play game with optional purchases), and mobile users are spending more time on Pokemon Go than on Facebook. Pokemon Go has become the most popular Android app for daily users, surpassing the previous leaders by nearly 300%. And it did that in a span of days.

Pokemon Go has taken the planet by storm. In its firstweek it surpassed Twitter for daily active users, it became the top grossing US iPhone app in just 13 hours (despite being a free to play game with optional purchases), and mobile users are spending more time on Pokemon Go than on Facebook. Pokemon Go has become the most popular Android app for daily users, surpassing the previous leaders by nearly 300%. And it did that in a span of days.

Not only have you likely heard of Pokemon Go, you’re also statistically likely to have played it if you have a mobile phone. If you haven’t played there are plenty of guides out there (here’s a video I thought was a good intro) or you can just go to any public place where you see people looking at their phones and ask them.

Given the meteoric rise of Pokemon Go, it is only a matter of time before the game crosses over into doing promotions and marketing activity. There are already reports that the game includes code to run a test promotion with McDonald’s in at least one Asian country. With this many people and brands interested in the hot new game (and eventual platform), my friend and fellow social media lawyer Jim Dudukovich and I wanted to present the seven legal issues you should know around the game for now. This isn’t specific legal advice, just us thinking about the intersection of new technology and the law. And an excuse to play.

1. Pokemon Go isn’t a platform…yet

While Pokemon Go provides an intriguing mix of real world and virtual world entertainment, the interaction between players is currently very limited. Players do not see other players while wandering their virtual map overlays on real world maps. The only interaction with other players is in lures dropped by players and battling/training at Pokemon Gyms.

The swirling purple flowers are caused by lures dropped by players–you can see the lures dropped by other players but cannot see the players themselves.

This is all certain to change in the future. The Pokemon Go terms discuss the ability to trade items with other players even though that functionality does not yet exist. Trading items with other players will possibly come with the ability to communicate with them as well, or perhaps there will be the ability to chat with other members of your team (one of three alliances you join upon reaching level 5 in the game).

While Pokemon Go has currently inspired people to get together and communicate, it is neither required for the game nor supported by it yet. So the game is not a social media platform…yet. But given the rise of players and pop culture awareness, it is almost a certainty that the game will either evolve to become a platform or players will start to congregate around another platform in order to communicate. This places the app more in the realm of just a game for now, but as it expands functionality and brands start to get involved there will be a number of common social media platform legal issues that emerge. So stay tuned. And level up in the meantime.

2. Sponsored content is coming

Where there’s a game, there’s an opportunity for brands to get involved (with varying levels of legality). The model for Pokemon Go has yet to mature (or at least to be announced publicly), but the ways brands can get involved will likely include not only some “conventional” methods, but also some integrations that are possible only with augmented reality.

Going forward, we are likely to see “official” partnerships whereby businesses can become sponsored locations or some other formally identified type of destination with yet-to-be-determined perks (and costs). In order to distinguish the haves from the have-nots, the benefits of paying for participation will need to really break through the clutter of the free-riders in order for businesses to invest (see #3 below). One would assume that part of that bundle of rights would be co-promotional rights, whereby those partners can produce advertising materials featuring elements that only official partners can use.

And with augmented reality comes the ability for brands to buy virtual advertising space; clearly Niantic – should it opt to pursue this revenue stream – will need to be thoughtful so as not to chase away users by overly commercializing the user experience. When users start having to walk around a virtual billboard in order to capture a Jigglypuff, they might begin to revolt.

3. But businesses are already cashing in

As things currently stand, some businesses are near Pokestops, which attract players to their locations to load up on Pokeballs and other virtual supplies and (hopefully) lead those players to buy something from the brick-and-mortar business; at the very least it breeds familiarity and exposure. We’ve also seen businesses buying and dropping lures to attract players, as well as putting up social posts that play off of the game’s name, notoriety, characters, and imagery, including using #PokemonGo. There are even online articles telling business how to take advantage of this claim, like this rather creative one from Shift Communications.

Some examples:

An electronics store in Austin, Texas advertising that it is also a Pokemon Go Gym.

This Brookstone in the Houston Galleria invites players in with a discount.

A post on social media shows an alleged poster by a Navy recruiter utilizing Pokemon Go, although this has not been verified.

Even Yelp has gotten in on the crazy by offering a filter to find businesses near PokeStops.

From a legal standpoint this raises some interesting questions. For instance, if businesses are leveraging the game to attract consumers, would Niantic not have a potential claim for false association/false endorsement? One would think so, but since it’s already been over a week and we haven’t seen any claims, uhm, wait – how long until some form of laches or abandonment defense would attach? But seriously – we don’t know if Niantic has any inclination to attempt to aggressively enforce its trademark rights – it’s making plenty of money from in-app purchases that are attributable to these uses and will likely make plenty more once it launches official branding opportunities. In light of that, so long as the participation by unaffiliated businesses doesn’t interfere with Niantic’s business opportunities to sell official partnerships, and so long as those unofficial users don’t hold themselves out as official sponsors or otherwise engage in behavior that could dilute or undermine Niantic’s trademark rights, we probably won’t see widespread aggressive policing.

4. Does Pokemon Go create attractive nuisances or encourage trespass?

Pokemon Go is not the first geolocation game to exist, but it’s the first to breakout in such a significant way. Having millions of people, many of them under the age of 18, wander around trying to collect virtual property brings some real property issues up in unique ways. These next three topics are just a few of those interesting overlaps between the real and virtual world.

Adults know not to trespass on private property (or the law infers they do) but children are typically given a free pass when it comes to attractive nuisance law. This is the body of law that covers situations when a child illegally enters private property and is injured while on that property. While originally laws in this space required the nuisance itself (piles of lumber, swimming pools, trampolines) to cause the injury, the law has also broadened the landowner’s culpability to include conditions that the owner could foresee would cause injury. Imagine a very visible giant pile of lumber that a child would want to climb and a ravine covered by grass on the way there–that’s covered.

The Pokemon Go terms do imagine this potential risk area. There’s an entire Safe Play section which discusses avoiding physical harm while playing and obeying all laws including trespassing. That doesn’t mean much to the 13 year old who won’t read these terms (and 99% of all other players), but it provides the developer with some protection around players being injured. The terms do not shield property owners, who now may face a slightly greater risk of some injury on their property by players looking for Pokemon. The game is designed to be played by walking around and the game informs players when Pokemon are nearby but not where they are–the only way to track them down is to try walking in different directions and seeing if they are closer to the Pokemon as indicated by the number of footprints near the Pokemon’s picture or outline.

Since Pokemon are placed randomly, it is possible the game could inadvertently provide clues that lead children onto dangerous property or near a dangerous condition. These clues are left vague on purpose, to make it more of an exploration game, but that also can lead children onto private or dangerous property. When the Pokemon finally appears you can click on its location in the map, but getting it to appear can be random. The game also gives you visual clues of where Pokemon might be with rustling leaves–players chasing those leaves may not realize where they are going.

The game itself doesn’t intend this risky behavior, nor can it be prevented currently. It’s also debatable if a landowner would be liable for a harmful condition when they did not create the attraction that drew a child onto the property in the first place. If a landowner is already in a densely populated area and is concerned about children being injured, they probably have already taken action (on the condition itself, preventing access, posting signs). If they are in a remote area it’s hard to imagine local Pokemon Go players entering their property as opposed to visiting areas of attraction (PokeStops which provide virtual items to players). But landowners in the space between may want to be aware of this risk and if they were debating taking action in the past, perhaps now is a time to do so.

While it may be difficult to pin responsibility on Pokemon Go for an attractive nuisance or trespass, it certainly creates an environment where those actions may be more likely to take place. So both players and landowners may want to consider the risks when playing.

5. Pokemon Go and the idea of appropriate play

Outside of the physical risks that players may be subjected to while hunting Pokemon, there is also a growing concern of whether playing the game is appropriate in certain locations. Within the first week of the game’s launch a story circulated about the Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC asking people not to play the game in the museum. Arlington National Cemetery also asked players to refrain from using the site as a playable location. The sites said they would reach out to the game creator to see about excluding the sites from the game but so far there does not appear to be an easy way for property owners to exclude their land from the game.

The idea of whether a location is appropriate or not is not limited to large national sites, though. Because Pokemon Go is based on work done for a previous geolocation game, Ingress, much of the previous game’s data are used for this new iteration. And because Ingress was based on a storyline involving spiritual energy, many of the featured locations in the game can have a spiritual element such as churches or monuments. Or take, for example, this PokeStop in Austin, Texas:

This happens to be the headstone for my wife’s great-grandmother Fania Kruger–a woman who immigrated to Texas when she was 15 and later became a well-known poet. Is her headstone being a PokeStop a good or bad thing? Is it a celebration of her life to have players intentionally seek out her final resting place and perhaps learn a bit of who she was or learn her name? Or is it a desecration of a place of remembrance for her and the other families whose relatives are nearby? While this may not present a direct legal issue, the reaction to a real world location with emotional interest becoming a game location can cause strong reactions. And those reactions may turn into legal issues as cemeteries, museums, or other public spaces must now develop a position on Pokemon.

6. Are Pokemon Go players loitering?

Laws vary on the subject, but generally speaking most jurisdictions have laws that allow authorities to prevent people from hanging around with no apparent purpose. Typically these laws were used to prevent gang activity or break up groups that might lead to trouble. With small or large groups suddenly appearing in public places, wandering around while staring at their phones, authorities might be curious or concerned. Within the first few days of the game being launched, a story appeared on Imgur of a white man searching for Pokemon in a park late at night only to encounter two fellow players, black men, and while the three of them talked the police were called about a suspected drug deal. The story ended happily enough, with the policeman downloading the game and playing, but under scrutiny the original poster deleted the story.

It is true that Pokemon Go is drawing out populations that were previously playing games indoors. While many people have long bemoaned the lack of America’s youth playing outdoors, society is also shocked and confused when exactly that happens. While businesses seem to be getting in on the action, some even advertising if their stores are PokeStops or Pokemon Gyms (areas where Pokemon are trained and players battle for control of the location), some other locations may be less open to random strangers driving up or wandering around. And authorities may be suspicious of large groups gathering at night. Is it a gang fight or a Pokemon Go meet-up?

The actual definition of loitering may differ by jurisdiction, but it is generally defined as remaining in one place without apparent purpose. Whether playing Pokemon Go provides that apparent purpose or not is debatable and may be up to the discretion of police officers depending on time and location. Shopping malls or other private property that have posted No Loitering signs are possible more sensitive to this kind of activity, so players may want to consider the area before conducting extensive searches or meeting up with other players.

7. Are Pokemon Go players targets for criminals?

In the wake of the game’s popularity came another rash of articles suggesting that players were at risk of being targeted by criminals. There was a report in St Louis of some teens who robbed players, possibly drawing them to their location by dropping a lure (virtual items which other players can see and increase your chances of finding Pokemon). It’s hard to imagine this is an actual spike in crime though–or if so it is by some of the worst criminals imaginable. Targeting Pokemon Go players seems far less lucrative than, say, staking out an ATM where people withdraw money. On the flip side, using a remote PokeStop may yield less rewards but have less chance of getting caught. Unless you’re in St Louis.

There’s also one story that made the rounds of a player who was stabbed while collecting Pokemon but elected not to go to the hospital so he could keep playing. You can read the full account here but I thought the more interesting (and usually ignored) part of the story was how he was out at 1 am, saw another man wandering around, and immediately asked him if he was playing Pokemon. This apparently triggered the man to attack the player with a knife. So maybe the lesson here is to not wander around after midnight playing Pokemon, or not to assume some other person stumbling around in the dark is doing the same. It may also be a lesson to the developers that hopefully they won’t create specific Pokemon that can only be found in urban centers, particularly near bars, in early morning hours.

More to come

Pokemon Go has certainly taken the country and world by storm but these are the very early days of the game. Will it fizzle in the upcoming months, or will it continue to draw a healthy crowd and new functionality as time goes on? We’ll keep our eyes peeled for any nearby rare Pokemon new legal issues around this game and let you know.

The 2019 Law & Social Media class ended back in May, but I totally forgot to share the final exam with everyone until now. My apologies, and here you go. How would you answer?

The 2019 Law & Social Media class ended back in May, but I totally forgot to share the final exam with everyone until now. My apologies, and here you go. How would you answer?